Shedunnit – Now and Then

The inspirations behind Dead Language and Other Stories. Part 1

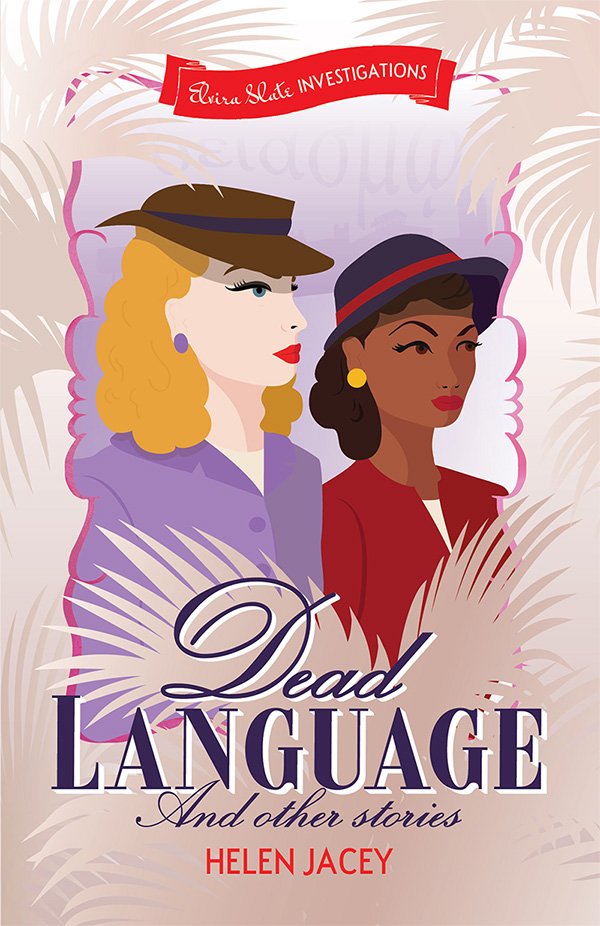

This 3-part blog is inspired by the talk I gave at the launch party for my new book Dead Language and Other Stories, one stormy night in St Leonards on Sea in November.

As the waves crashed onto the shingle only yards from the jazzy venue, I condensed three years’ worth of writing inspirations into fifteen minutes. Respect your audience (who after all also came for all-girl swing music, solve a murder mystery, and slugging Dirty Shirley cocktails)!

For those of you who are writers or readers, or perhaps Elvira Slate fans, these three blogs will see me investigating my inspirations behind writing Dead Language and Other Stories. Part 1 looks at how the past and the present creatively stimulate my historical crime writing.

THE SELF-PLEASURE PRINCIPLE

…in writing! Amongst many things, we historical fiction writers juggle several balls – being ‘authentic enough’ in our work, appealing to those we hope will become our regular readers, all the while satisfying our own aesthetic desires and ‘authorial intentions’.

Not so easy to keep all the balls in motion. Pleasing all the people all the time is nigh impossible.

When in doubt, please yourself. Write the book you want to read.

After all, as readers ourselves don’t we tend to seek out books that reinforce our values and word views, even if the subject is new? Books where we like the protagonist and support her goals?

Writing historical fiction is both a highly self-indulgent process, especially if you weren’t born in the era, as well as being pretty hard work.

On the enjoyment side of things, you are a time-traveller, visiting past worlds at the same time as fabricating your own.

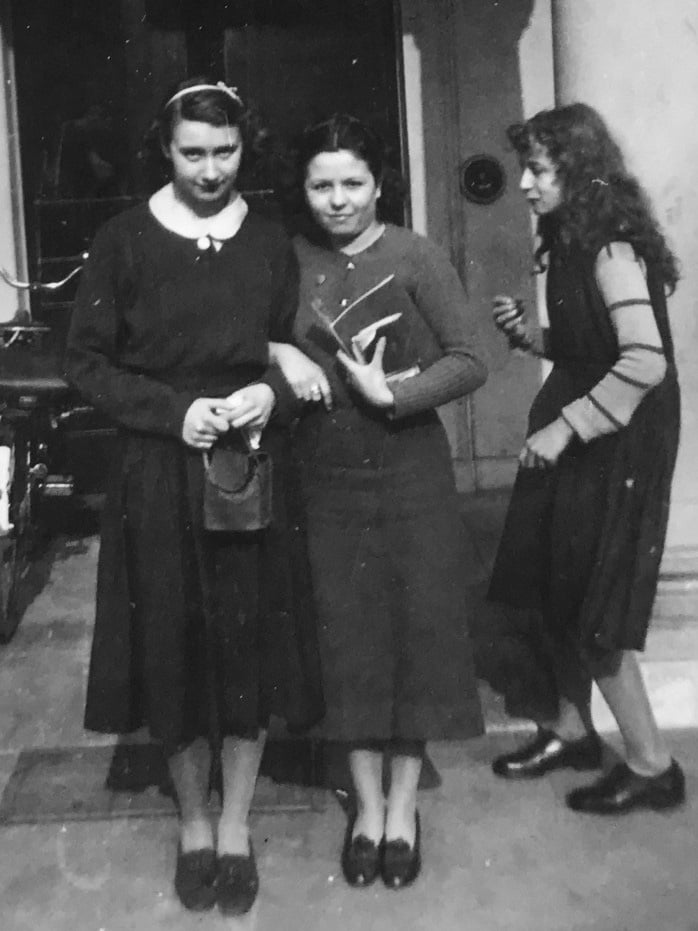

You plunder from all manner of sources and resources to suit your vision – your lived experiences, your family history, your reading, your viewing, your listening, on top any conventional ‘historical research’.

A bit like venturing into a pic ‘n mix creative candy store.

You can make uncanny discoveries, often when you least expect.

Like my discovery of the original-coloured photographs of Southern California in the 1940s, by Edward Alinder.

The more you immerse yourself in your world the more joyous and serendipitous these can discoveries feel.

Your historical world gradually emerges with its own truth. Like beauty, it lies in the eye of the beholder.

Yours.

VINTAGE STORYWORLD BINGE-SHOPPING

Pushing the shopping metaphor, the 1940s world that lurks in my creative conscious is rather like a cluttered vintage shop.

Rails of 1940s fashion, tailored suits and flowing gowns. Bookcases stuffed with old books on Greek mythology and psychoanalysis. Walnut cabinets full of crockery and cocktail glasses. Counter tops sparkling with rhinestone-encrusted costume jewellery. An old curvy wireless blares out 1940s swing music. Vintage magazines lie open, revealing stylish adverts from the era…

You get the idea…a shamelessly nostalgic place, defined by the addictive style of the era.

Society’s values of the 1940s are, however, something else. Leaving the symbolic vintage shop, I enter a more complex world that fuses 1940s style with a female gaze.

Shedunnit uses #bookswithvintagestylenotvalues on social media for a reason.

A WOMAN’S WORLD

A guiding creative star to the journey into a more complex and relatable 1940s noir world, is my ‘conviction’ that some readers will want to travel there with me, who share the sensibility of loving a vintage world, yet being progressive.

Outside there is sunshine, palm trees, the pacific and the winding desert roads, department stores, yellow taxis, limousines, trolley buses. And there are the ‘requisite’ venues of 1940s noir: scenes of the crime be they bedrooms, ballrooms, offices, or the hot desert; the City Morgue, the Palace of Justice and County Jail.

But ‘truth’ of the world comes in another form: the nightclubs for lesbians and queer women where all girl swing bands play, city clubs where women do business with each other, motels where hot sex takes place, female private investigator offices, hotels for women, French patisseries, beauty parlours and boarding houses.

Across the Atlantic, the dusty streets of a bombed-out South London, walk past rows of gloomy terraces, craters where a home once was. And going further along the walk, the brick walls of jails, beyond these the cells, dark, dank, and cramped.

Further on, the leafy grounds of Sussex Reform Schools, belying the austerity, the cold dormitories, the locked cupboards housing the cane, the refectory’s long tables. The hidden yet outwardly respectable places of punishment and child abuse.

The places of women and girls who didn’t fit the norms from their perspective.

TROPED TO DEATH

Ex-cons, LGBTQ+ people, racially diverse communities, older people, disabled people and mentally ill people – anyone who didn’t fit the 1940s notions of wholesome – had let’s face it, dire representation.

They rarely got to tell their story, and when their ‘problem’ was featured, storytellers had to tread very carefully.

I call this toxic invisibility death by trope.

As far as women were concerned, 1940s crime and noir stories were more interested in to what extent women conformed to idealised notions, and if they didn’t, how they would be punished. I’ve talked about this here.

In Elvira Slate Investigations my characters are complex, dimensional women who juggle and do their best to meet their emotional, physical, creative and professional needs in the limited 1940s – however limited.

In Dead Language and Other Stories you will meet – through Elvira’s eyes – all kinds of women; diverse in all ways; women who make, women who love other women, women who run businesses, mothers who love, women who like other women, women who don’t.

Elvira is a flawed and complex human being, so I have to juggle another ball – Elvira’s attitudes to people in her first-person narration. Her changing values, growing compassion and awareness – which increase as she ‘heals’ versus mine, her creator.

I want her to be relatable, an outsider, a woman ahead of her time but also ‘authentic enough’ in her attitudes.

My intersectional feminist revision of the 1940s in Elvira Slate Investigations probably won’t satisfy fans of Miss Marple, however transgressively one reads Christie.

A TENSE PRESENT

As much as historical fiction writers are immersed in our revisions of a past period, we cannot write inured from current events. Whether we choose to be ‘conscious’ of this or not is another matter altogether.

Three out of five of the stories in Dead Language and Other Stories were completed during the pandemic.

It was poignant, as somebody whose stories are set in the 1940s, with characters who have lived through the war, to now experience the pandemic’s collective sense of danger and death, closed borders and trapped lives.

Missing my own family, friends, hearing sad tales of loss and isolation from my creative writing students who I was teaching online, meant that lockdown life for many of us was permeated with a sense of loss and anxiety.

The new norms we adjusted too were not just physical, they were emotional.

And, for me, I believe this crept onto the page. The resulting stories in Dead Language are mysteries of the heart. Elvira’s cases explore themes of yearning, guilt, love and loss.

Why do we love? Who do we fight for? Who do we sacrifice? Who do we abandon? Who will we never forget, or forgive?

My present influenced Elvira’s cases in Dead Language and Other Stories. In essence, they are more ‘Why shedunnit?’ than ‘whodunnit’.

To solve these cases, to reveal their truth, Elvira Slate, as resilient as she is fragile, needs to confront her own deep psyche, an unlikely ally to her intuition, the most vital tool in detective toolbox.

She will have to talk to her Dead.

Helen Jacey

© 2023 Shedunnit Productions